Ancient Korean Song Stays Strong After 11 Centuries

Ancient Korean Song Stays Strong After 11 Centuries

Posted May. 12, 2008 03:07,

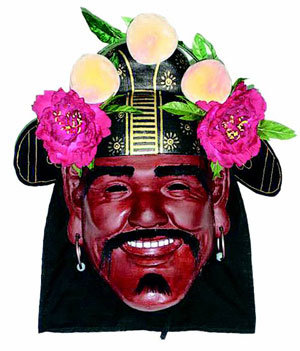

The ancient Song of Cheo-yong dates back to 879 A.D. during the reign of Shilla Dynasty King Heongang. The Korean tune has resurfaced thousands of years later in the modern world under various representations, and has served as a motif in art covering genres such as dance and music.

Likewise, hundreds of Korean scholars have expressed their thoughts on the song through academic papers. Heo Hye-jeong, a creative writing professor at Korea Cyber University in Seoul, said, I have never seen a cultural theme of such power that has survived 1,100 years.

Earning a Ph.D in modern literature from Dongguk University in Seoul, Heo eventually dedicated herself to studying the song. She said she was attracted by its charm and the theory she learned as a college junior that Cheo-yong might have been an Arab merchant. She then began exploring references and literature to support the theory, to which no one paid attention at the time.

Her long journey has reaped other perks. Heo has discovered the value of the song as commercially-viable cultural content. She calls the song the most valuable cultural heritage of Korea that can survive in and fascinate the global community.

She has published a book on the song that explores its value and proposes ways to use it as cultural content.

I have found validity in the theory that identifies Cheo-yong as an Arab merchant from ancient Persia, she said.

First, she quotes lyrics from the song, which read:

Under bright moonlight

playing around deep into the night

I came back home

To find four legs in my bed

Two belong to me

With two others belonging nowhere

Now, mine are no longer mine

But I can do nothing

Songs from the ancient Shilla Dynasty are mostly about patriotism and encouragement of Buddhism. Thus, a song about adultery and eroticism was a break from the mainstream at the time, Heo said.

Adultery and extramarital affairs of queens constitute the main themes in the beginning chapters of A Thousand and One Nights, she said. Here, the pattern repeats itself. The Persian emotional pattern depicting free sex matches the pattern shown in The Song of Cheo-yong.

The dominant theme in Persian art in the seventh and eighth centuries was stealing other peoples lovers, something consistent with the dominant theme in the song.

History-wise, Shilla imported a considerable volume of Western and Middle Eastern civilization through the Silk Road. Heo said this makes it highly possible that the songs title referred to an Arab. Furthermore, the description of Cheo-yong in an ancient history book depicts him as an Arab man.

Of course, we have lots of different interpretations, Heo said. But when we look at historical facts, features of ancient Persian civilization and the depiction of Cheo-yongs appearance in literature, Cheo-yong must have been an Arab man.

The exotic features and charm of the work and Cheo-yong must have encouraged different representations of the song throughout the ages, the professor said.

We have used the song and its theme in diverse genres, she said. We have used it to create musicals, operas, novels and poems. But we have made no effort to systematically manage it as our cultural heritage.

Heo recalled how hard it was for her to look through volumes of references without an established database on it.

The Song of Cheo-yong stands out for its cultural uniqueness, she said. At the same time, it contains universal elements of global culture. Its really unique in this respect, conveying huge potential as a motif for various types of digital culture content such as animated games. Thats why we need a systematic approach and management of the work.

The professor said the Glory of Persia exhibition running at the National Museum of Korea will significantly raise understanding of the song, saying the work must be understood in the context of Persian civilization.

gold@donga.com